This Is What Happened To The Missing Trans Women Of El Salvador

The story of how a group of trans women vanished in the midst of El Salvador's civil war has been passed down from generation to generation, creating a legend that gave them a place in the history of a country that often seems to wish they would disappear. BuzzFeed News' J. Lester Feder set out to document the mysterious incident for the first time.

Posted originally on Buzzfeed News on December 27, 2015, at 10:18 a.m. ET

SAN SALVADOR — La Cuki Alarcón was late to work on the night that his roommate disappeared, which is why he is still around to tell what happened.

His hair was extravagantly curled, and he matched a long skirt with high boots, a look he hoped hid his legs, which he thought looked too manly to appeal to his clients.

Alarcón was hurrying to the strip they used to work across the street from El Salvador’s national symbol, the Divine Savior of the World monument, a statue of Jesus with his feet planted on a globe perched atop a column about 60 feet in the air. Work was so steady on that corner that Alarcón thought a client might have already picked up his roommate and the other locas they hung out with. Outsiders called them all “homosexuals,” but the sex workers — some who lived as women all the time, others who dressed as women primarily on the job — called each other “crazies” even though some used it as an insult that would roughly translate to “sissy.” (Alarcón asked BuzzFeed News to refer to him using male pronouns.)

As Alarcón reached the opposite corner, he could see his friends were still there. He hesitated for a minute before crossing because the stoplight was out, and that’s when he realized the locas were not alone. Four tall men in ski masks were throwing them into the back of a green truck, clubbing them with the butts of their guns.

Alarcón remembers the year as 1980, a time when death squads were using trucks like this one to make people disappear by the hundreds every week. This was the beginning of the civil war that consumed El Salvador until 1992. The United Nations, NGOs, journalists, and scholars have sought to uncover what happened to many of the more than 75,000 who were killed or disappeared during the conflict, but no one has ever investigated what happened to Alarcón’s friends. As far as anyone knows, no one has even recorded their names among the missing.

But Alarcón can still rattle off the names of many of the dozen he remembers being thrown into the truck that night. There was his roommate Cristi, whom he remembers as a gentle 26-year-old who would bring him gifts of coats or shoes from trips she’d frequently make to Guatemala and Mexico. Another was Verónica, from San Bartolo near the Honduran border, who was so pretty that her clients would sometimes insist on having their pictures taken with her. Carolina was so well put together that she’d sometimes get into trouble — she looked “all woman,” Alarcón said, and her clients could get violent when they discovered she was trans as she undressed.

Alarcón is one of the only witnesses to their disappearances who is still alive, but the story of that night is well-remembered. It has been passed down from generation to generation of trans sex workers in the country’s capital, San Salvador. It’s been retold so many times it can sometimes be hard to separate fact from legend, passed down in the same way many families retell the haunting mysteries that still linger from the war. The tale stakes a claim for trans women in a country that often seems to wish they would disappear.

“Maybe there still could be some justice for us, right?” Alarcón said during an interview in San Salvador last December. “Maybe remembering everything that happened to these friends can bring some peace for all homosexuals?”

I first learned about this story from a 38-year-old Salvadoran trans activist named Karla Avelar in the fall of 2014 while working on a story about LGBT kids fleeing the country to make the dangerous, illegal trip to the United States. El Salvador has some of the highest rates of anti-LGBT violence in the hemisphere, and Avelar recounted waves of unpunished murders over the past several decades. In 2014 alone, at least 12 women and two gay men were killed, according to media reports. There was the “Bloody June” of 2009 in which at least three trans women and two gay men were murdered. Avelar herself survived being shot in the 1990s by a serial killer who had been gunning down trans sex workers.

The ones taken from the Savior of the World were almost mythical to Avelar, who was a baby when the events occurred.

“We don’t even really know much ourselves, but a little while ago one of the survivors told us what happened and said to us, ‘Why don’t you document this, that I was a victim of that attack?’” she said. But the task seemed impossible. “There is no documentation whatsoever, no publication nor record — there is nothing.”

Avelar knew of just one witness who still survived, a woman named Paty who she said was 78 years old, a miracle in a country where violence and HIV are so widespread very few trans women survive to middle age.

“They said that they had dressed them up as soldiers and made them play war”

I flew to El Salvador as soon as I could. Paty’s health sounded fragile and if she died before her memories could be recorded, any hope of documenting the atrocity would die with her. I decided to work with Nicola Chávez Courtright, co-founder of a small organization documenting the history of El Salvador’s LGBT movement called AMATE, hoping she would have ideas on how to start substantiating Paty’s memories.

When we visited Paty — whose full name is Patricia Leiva — shortly before Christmas last year, we learned that much of what Avelar told me was wrong. Leiva was only 60, though it was understandable why Avelar had thought she was much older. Health problems had swollen her stomach like a basketball and made it nearly impossible for her to walk. She also had not been there on the night of the disappearances from the Savior of the World, and years of heavy drinking meant she could only recall bits and pieces of the story, despite having heard it countless times.

Leiva lives in the remains of what used to be a popular beer hall called the Bluegill in a once-thriving red-light district called the Praviana, now subdivided into tenements. The bar had belonged to La Cuki Alarcón, Leiva told us, and he had been there that night.

Alarcón is now retired and lives in the suburbs, surviving with help from his children who live in the United States. Alarcón doesn’t routinely go by “La Cuki” (a Spanish spelling of Cookie) anymore, preferring his male name. But he asked that we not publish his legal first name because he was worried about his safety for talking about the war. Besides, he said, “La Cuki” had been “my nomme de guerre — my homosexual one.”

Alarcón hid from the men rounding up his friends that night by throwing himself to the ground in a small garden. He tried to slink away after watching the men pile his friends into the truck, but more armed men were patrolling the surrounding streets. He remembered making it to the La Religiosa funeral home up the block, where he tried to take sanctuary, but he said the guard wouldn’t let him in because there was a lavish wake underway — “There are only famous people in there,” the guard told him. So he waited out the raid crouched between the cars parked outside.

When the coast was clear, he went back to work on the corner. Within minutes, a client had come and picked him up. Alarcón figured he’d see Cristi in a day or two, which is how long the cops usually held sex workers after a routine vice raid.

But Cristi never came home. None of them did.

Alarcón went to the police stations to try to find her. He even hired a lawyer. But the cops made fun of him and hinted that his friends were already dead.

“They said that they had dressed them up as soldiers and made them play war,” he remembered.

“Maybe there still could be some justice for us, right? Maybe remembering everything that happened to these friends can bring some peace for all homosexuals?”

El Salvador’s 12-year civil war had its roots in political battles that had been going on for half a century. In 1980 it blew up into one of the last and bloodiest conflicts of the Cold War. That year, military leaders ousted moderates in the ruling junta while paramilitary squads aligned with the regime hunted down government critics. The war vaulted into international headlines in March, when the head of the country’s Catholic Church, Archbishop Óscar Romero, was shot through a church doorway while he was celebrating mass.

The U.S. government threw tremendous weight behind the military leaders even as the body count grew, and a rebel force called the Farabundo Martí National Liberation Front fought back with a little support from Nicaragua and Cuba. Echoing the early days of Vietnam, Washington sent in military advisers, contributed tens of millions of dollars in military aid, and trained Salvadoran troops at an installation in Panama known as the School of the Americas. The U.S. continued this support even after reporters for the Washington Post and New York Times uncovered that a U.S.-trained battalion was responsible for one of the war’s most infamous atrocities, the extermination of an entire farming village called El Mozote in 1981.

The two sides were locked in a stalemate as the Cold War came to an end with the Soviet Union’s collapse. Peace accords signed on Jan. 16, 1992, made uncovering the crimes committed during the war a cornerstone of rebuilding the nation, creating a Truth Commission run by the United Nations to gather witness statements and write a definitive account of the war’s greatest atrocities.

Because many of the war’s abuses were so extensively documented in that process, we thought we might find some record of the disappearances from the Savior of the World. But we came up empty. Our best hope was the archives of the two human rights offices run by San Salvador’s Catholic Archdiocese — the most active human rights monitors during the war — but they could locate no records matching the case. They might have been able to search more if we could provide the victims’ legal names, but Alarcón and the others we spoke with only knew them by their female names.

We had hoped that El Salvador’s oldest gay rights organization, Entre Amigos, would be able to help us substantiate these memories. When it organized the country’s first pride march in 1997, the group declared it as a commemoration of another event said to have happened during the war years: the abduction of a number of trans women from the heart of the Praviana red-light district by a U.S.-trained battalion in June 1984. This is the one case of crimes against LGBT people claimed to have been recorded by human rights monitors during the war.

Entre Amigos’ co-founder William Hernández told us in an interview that he had uncovered a statement from a witness to that incident while working in the archive of an organization called the Nongovernmental Human Rights Commission just after the war's end. But, Hernández said, the account was so confusing and incomplete that, when examined “from a legal point of view, it wouldn’t give me anything that argues that this was real.”

He initially said that he would be glad to dig it out of the group’s files for us anyway, but he grew increasingly combative when we attempted to follow up. Finally, he sent us a note saying his lawyers did not “trust how the information will be managed” and requested that we remove reference to Entre Amigos from this story.

So we went directly to the Nongovernmental Human Rights Commission, and they told us they could not locate any such testimony in its archives. None of the people we interviewed said they’d witnessed an abduction as described by Entre Amigos or knew of anyone who had. If the testimony existed and it was as mixed up as Hernández described, there’s the possibility that the person was describing the disappearances from the Savior of the World and some of the details got scrambled in the retelling, including the year.

And we could never pin down the date of the disappearances for sure. It’s not uncommon for people to have difficulty remembering dates from the war years — even when loved ones died, the violence was so unrelenting that the number on a calendar seemed like a fairly meaningless abstraction in daily life, other reporters who covered the conflict told us. Calendar dates might even be especially hard for the trans women we interviewed, most of whom didn’t finish elementary school because they were thrown out by their families once their femininity became apparent.

The witnesses we interviewed mostly gave dates ranging from 1978 to 1980, but the fall of 1980 seems likeliest. One person who lived in the Praviana at the time told us she remembered they were still searching for the missing when one of the most notorious killings of the war took place: the rape and murder of three American nuns and a laywoman by the National Guard on Dec. 2, 1980.

This timing may be confirmed by something we found while paging through three years of newspapers from the period, held in dusty binders in the collection of San Salvador’s Museum of Anthropology. The only announcement for an event at the La Religiosa funeral home we found was published by both major dailies, El Diario de Hoy and La Prensa Gráfica, on Oct. 1, 1980. It was for a man who had died in Los Angeles, California, whose remains had been shipped home for burial, suggesting he may have been from a wealthy or important family. Alarcón remembers the wake where he tried to hide from the raid as being especially fancy, so there’s a possibility this was it.

That’s not a lot to go on, but two days later, El Diario de Hoy reported that police were leading sweeps to “purge those elements that are undesirable to society” in response to recent thefts. The operation was reportedly focusing on a park about two miles away from the Savior of the World — though close to the Praviana — but the next day La Prensa Gráfica quoted police saying the effort was expanding to target “other sites known as refuges for criminals.”

It may be hard to imagine a dozen people could disappear without attracting some attention. But at that point in the war, unexplained deaths had become so routine that it was remarkable when anyone raised a fuss. (And these were sex workers — trans ones at that — the kind of people whom many would probably have been happy to see cleared off the streets if they noticed them at all.)

Bodies were being dumped at a rate of more than 150 a week, which the U.S. Embassy would tally in regular “Violence Week in Review” cables, even as the U.S grew closer with the El Salvadoran regime. Remains were found scattered around the capital every morning, sometimes with their faces destroyed so they could not be identified or left in a spot where vultures could be counted on to scatter their bones. Trucks like the ones Alarcón saw at the Savior of the World were icons of the inescapable violence.

The death squads’ victims were “killed in the usual fashion,” reported a cable from the U.S. Embassy to Washington of the 179 people who died in the week ending Nov. 28, 1980: “Kidnapped by a group of armed men who appeared as civilians, taken away in the ubiquitous pick-up trucks, shot or strangled or both, and then dumped along roadsides.” Six of that week’s murders included top opposition leaders that attracted some outcry, the cable noted, but their deaths were “unusual in that they have gone noticed.”

If news of the death of a group of sex workers had reached officials at the U.S. embassy or human rights organizations, it could have easily been ignored as an extreme vice raid rather than as a political crime.

But those who lost their friends believe they died because of politics. The most intriguing part of the legend of the disappearances from the Savior of the World — and the part that is probably the most impossible to pin down — is that they were killed to cover up a government secret.

They were taken that night, the story goes, in a hunt for two sex workers who had evidence of a crime. Evidence they had stolen from an American.

Some of the locas thought the American was a diplomat, while others believed he was a reporter. No one really knew why he was in the country, but they all knew what he looked like. The ones we spoke to who had seen him recalled that he appeared to be in his fifties with close-cropped white hair and a mustache or a goatee. He was a big spender who always hired two at a time — “one for him to make love to while the other made love to him,” one person told us.

They were taken that night, the story goes, in a hunt for two sex workers who had evidence of a crime. Evidence they had stolen from an American.

The two he picked up shortly before the raid stole his briefcase. Inside were some cameras that the locas believed had been used to photograph some kind of a government crime.

All this might be easily shrugged off as the kind of conspiracy theory that proliferates in wartime, except several sources said they’d heard it from people directly involved. La Cuki Alarcón said the American came to his bar offering a reward to get his cameras back. Another sex worker, who asked not to be named, said she’d been warned that a hunt for the thieves was underway by a sergeant in the National Guard who was her regular client. Several told us that one of the thieves had a wife, a cisgender woman named Sonia who lived in San Salvador for at least another 30 years and would sometimes talk about how the authorities eventually dug the briefcase out of her patio with the cameras still inside.

Everyone believes both thieves escaped, but there are a lot of different stories about what happened to the ones who disappeared beneath the Savior of the World: They were tortured by having their fingernails pulled out and their breasts shorn off. They were dragged to death by horses at the infantry barracks. They were dumped in a hole on the road to the notorious Mariona prison.

Their families tried to find them. A woman named Yazmín Zulema Enríquez, whose mother did laundry in a Praviana brothel, told us how relatives of the missing would come for help with their search. She remembered being left in charge of the brothel when the owner would personally make the rounds of the offices of the National Guard, the Treasury Police, and the National Police. The men said to have taken the locas away wore no uniforms, so there was no way to be sure which force had taken them.

“We didn’t even hear of any of [the locas] being held prisoner,” Zulema told us. “Of all the ones they carried off, not even cadavers were found.”

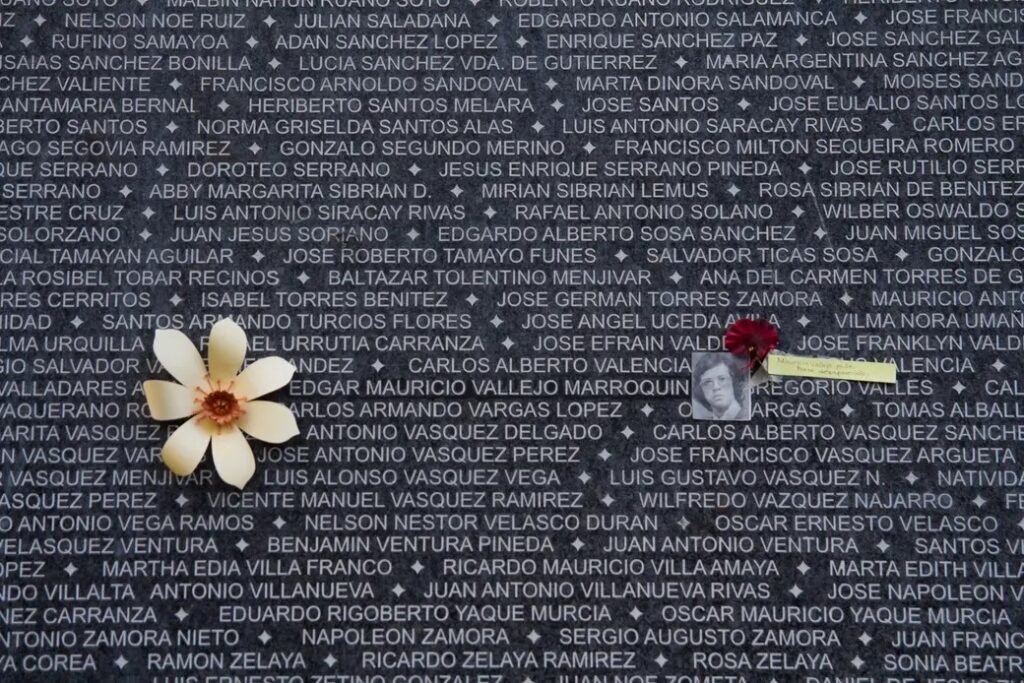

El Salvador is filled with stories like these, people turned into ghosts because unanswered questions are all that remains of them. A monument to the dead and disappeared that was unveiled in San Salvador in 2003 now bears the names of around 30,000 dead or disappeared who have been documented. Another 45,000 are estimated to be missing from that wall, a number that includes the ones who disappeared beneath the Savior of the World.

Unexplained death became even more common for the trans women of San Salvador after the war. They were victims of the gangs that took over San Salvador’s streets, or targeted in drive-by shootings, or killed by HIV. By the turn of the century, the Praviana — which the sex workers say was home to dozens of trans women around the time of the war’s end — had essentially ceased to exist.

All that’s left is what remains of the Bluegill, with Patricia Leiva living in its carcass. Her home is a small room with a beat-up pallet on a concrete floor for which she pays $3 per day. She survives primarily by selling a few Coca-Colas and packs of gum from her door. She also still turns the occasional trick, though she can only walk a block or so on a good day.

She lives about a mile from the Monument to Memory and Truth, and her rusty shack is the closest thing to a memorial for the friends who passed through it. If it is too late to find out who killed the ones who disappeared beneath the Savior of the World, they at least want their memories to be believed.

Leiva showed us her ID card when we asked if it was safe to publish her name for this story.

“Use my name!” she demanded. “This is serious what we’ve talked about. And we’ve told the truth.”

UPDATE

January 4, 2016, at 11:39 a.m.

This story has been updated to clarify the nature of the document that Entre Amigos claims to possess.